Research and design

Before beginning actual sculpture, I study subjects extensively, both using typical searches for reference photographs (and following a large set of talented macro photographers), and using the scientific literature. In many cases–such as for the underside of most arthropods–few photos exist outside of the taxonomic literature. Even when pictures are available, understanding what one is seeing often requires considerable research. The details of a wasp’s mouthparts, the anatomy of a barnacle’s cirri (feeding appendages), the precise structure of a trilobite’s biramous (two-armed) appendages…all of these have proved to be deep rabbit holes. Only by immersive research can I develop the mental model of a part sufficient to begin design.

Design begins in 3D software. I use Blender, a free, open-source 3D modeling program which is notoriously challenging to learn but is also enormously powerful. I use only a tiny fraction of its capabilities. Mainly, I begin with simple primitives–spheres, cubes, planes–and push, pull, and combine them until the proper shapes emerge. Despite the fact that I am sculpting, I rarely if ever use the typical “sculpt” functionality of Blender. This gives my work its characteristic blend of simplicity and detail.

Engineering

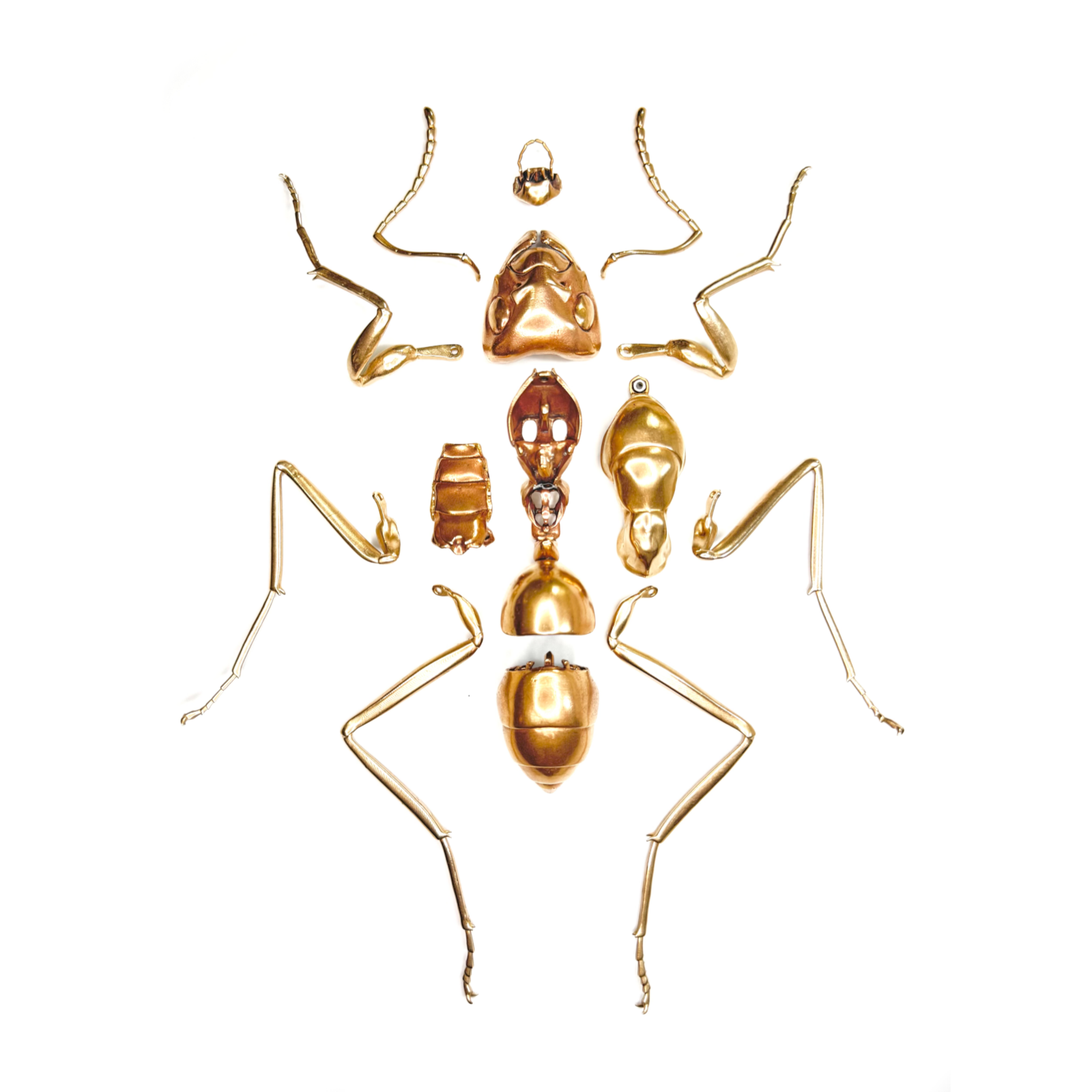

To achieve high levels of detail for larger works, while also producing parts which can be cast reliably in jewelry-scale flasks, I have converged on a process of engineering and assembly. Engineering becomes essential when pieces are articulated. Producing these complex assemblies involves breaking the subject down into separate parts, then designing the means by which the parts will be assembled into the final piece: holes for bolts, cradles for nuts, snap fits, magnet mounts, and so on. Part of the enjoyment of making a piece is solving a series of engineering challenges. Often, this involves iteration using 3D printed models until the assembly process works smoothly, and only then transitioning to metal.

Casting

Resin patterns are turned into metal parts through the ancient process of lost-wax casting, or investment casting. Since 2024, I do most of my own casting in my studio. Bringing this complex process home rather than working through partners, while creating complexity, has offered greater levels of control and scale. I cast both bronze and silver using similar processes.

Assembly

Most works are composed of multiple pieces to be assembled.

Finishing

Finishing involves patination (surface oxidation) and multiple levels of polishing.